EN

°1964 in Ninove, Belgium

‘The re-contextualization or transformation of an image stands at the center of Rik De Boe’s charcoal drawings. Humble in scale, the works utilize a point of departure embedded in collective memory. The pictorial details depict ordinary yet powerful visual triggers derived from movie stills, daily objects, and so forth in the service of the black and white modulation—leaving memorabilia rather than drawings. Like Xerox copies of our collective consciousness de Boe’s realism reverses interpretation and manifests images as forensic evidence.’

Marc Hungerbuhler 2010

‘Wat later zal zijn, daar is men buiten’

Piet Mondrian

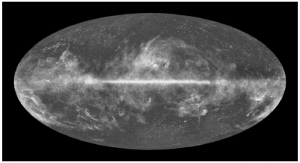

Rik, we’re on the sky map! Thanks to the satellite called Planck. Science found out that mankind and its Milky Way delimit the centre of the universe. What a useless but comforting thought. Our solitude couldn’t be more complete; infinity begins here with us and puts us in the limelight: I imagine other forms of life having fun watching us on huge projection screens.

I have often wondered how many cameras spread all over our planet simultaneously click. Or say tshack. Above Brice Canyon, at the gates of the Forbidden City, on the slopes of the Mont Blanc, under the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, in Swiss living rooms: I listen to the deafening sound of all those motionless movements. Then I try to imagine the thus perpetuated scenes and the sight of the crazy collection they become part of. Thereupon I imagine all the possible actions a human being is capable of: sexual acts and violent deeds, birth and its consequent death, stirring in cooking pots, developing photographs, building a house to live in. This condition humaine (> R. Magritte) is already captured in the shutter speed. A fraction, I hear someone whisper. How short life is and how long art. Or how time irreparably flies. Time coagulates the actions captured by the tshacks: a recording as if of the dog of Pompeii, the fate of the crew inside the Koersk or the Chilean miners 700 meters below our feet.

In the story ‘The Tram Race’ by F.B.Hotz (1922-2000), ‘a wonderfully beautiful, vibrating story of a race between protestant and the catholic villagers’, there is this remarkable case of a twist of time. ‘The race between the two steam trams, with the two groups of peasants on both sides of the rails glistening in the sun, ends in a horrendous way. But the narrator lets a kind, wise God, gently watching His poor overexited creatures, intervene. God puts the clock back, lets a peasant craving for penance get knocked down by the tram and the balance in the village is re-established.’ The mysterious film ‘Stellet Licht’ (Carlos Reygadas, 2007) ends in a similar, fairy-tale like manner.

In this book of yours one should use the word alarming in addition to wonderfully beautiful and fairy-tale like. What happens to all the knowledge built up by our dead, to the languages they spoke, to their gestures, their habits and the small house-garden-kitchen traditions they created?

An old caretaker, slowly and seemingly aimlessly shuffling about in the huge mansion and now and again, as he passes the door of a room, locking it cautiously. Inside the room an unbearable silence gathers and in its twilight a greyish light anxiously shines upon the last witnesses of human presence.

For what reason do I here (at this point in the book) think of Mao’s Great Sparrow Campaign, part of the Great Leap Forward at the end of the Fifties? Millions of Chinese farmers were gently forced to go out into the fields and bang on pots and pans so as to exhaust the sparrows to such an extent that they would literally drop dead. The plan had an immediate though partial effect: the Chinese fields were covered in dead birds but the following year grasshoppers, now freed of their natural enemies, caused an unequalled though collective famine.

One of the most beautiful palindromes in Dutch also comes to my mind: meetsysteem. (measuring system)

Each day, it gets light and then dark again. We built night and day around this feature and linked certain sensibilities to it. We build, that’s what human beings do. As I said before, Rik: there’s a parallel path running next to the general pavement of conventions: I think it’s where Art is staying: right next to the path of construction.

The image of Philippe Petit balancing between the WTC towers in the film ‘Man on Wire’ (2008) by James Marsh (almost naturally) darts through my mind but it is immediately followed or so to speak replaced by this feeling of a vacuum in space and time: Where are those towers? Where is the crossing? Where is Petit? What actually happened? There is only the exceptional documentary that bathes in vanishing.

Or I can see myself once again: there is a picture of a woman by Lake Como: a woman standing in front of a southern cultural landscape. The lady is posing graciously. On a second level there is a river that seems to separate two realities: an ‘eternal’ natural landscape (the mountains in the distance) and cultural landscape (the city in the background) and the less eternal condition of living beings (there are also a few palm trees), cameras and road markings. Strange to find out that dead things live longer. On the river a speedboat seems to enhance the contradiction. The woman looks exactly like a woman I used to know very well although never at her age on the picture; she is certainly younger than I am now. It is as if time, as a distance between the two ages, never went by. As if you could travel faster than light and catch up with images and events (history).

Apparently, I am inclined to think in images and the question whether or not we dream in colour doesn’t seem to bother me.

The white in your drawings is whiter than the white in your drawings. I experience the shades of one colour, visible grey tones, but even blue and red. A non-colour actually. Maybe some years cannot be classified as ‘before’, because too little ‘happened’ in them.

It’s as if the drawings autoperish, by the force of their own strength, because there doesn’t seem to be a ‘before’ or an ‘after’. They deal with a moment something is about to happen, a moment just after something happened; a non-event which, because of its nature, stays out of reach of the unexcelled internet memory and the Google Archipelago or which on the contrary derives its character from it.

An attempt to avoid the existing constructions by , yes indeed, building a new one, although this time while being fully aware of the process.

Piet Mondrian loved dancing.

In the house in which I was to become an astronaut, stood a TV set that was chronically ill. At the simple request of my father a friendly repairman would each time come along. He was always just in the neighbourhood. The repairman’s name was Werner and combined with his surname, which is of no importance here, he became and remained linked to black and white test patterns and the 50 Hz-buzz of lamps. I have a clear image of the black and white test pattern, almost as the highest individual form of collective memory. A test pattern in colours, however, I need to imagine (if the need occurs).

In order to suggest a standstill, an assumption of movement is essential. A standstill or lack of movement in most photographic images is so different from the one in your drawings. We are of course familiar with the time-freezing property of photography, but aren’t there wheels within wheels? The quality of the movement suggested by the drawing as well as the standstill that follows are of a more individual kind, determined as it were by the viewer; older photographs seem to share this characteristic, but that’s partially based on appearance. Moreover, the viewer often needs to be better at projecting himself into the past. So with drawings, it’s different.

White spots and areas or alternatives loom in practically all the images this book features. I’d call them blind spots in collective memory. The space around them is contained in precisely outlined forms that nevertheless seem to be strongly absent – the restored damage of frescoes irrevocably evokes the entire image and presents the viewer the actual mission: to give the work of art a reason to exist by reshaping it, by remembering it, so to speak. The viewer on page 18 looks as if he doesn’t see a thing. The lady on page 70 also experiences trouble with distance. The viewmasters become contradictory and cannot possibly live up to their names. On page 77 the content of the book seems invisible also to the readers. The flowers and the light on the hospital night table on page 134 reflect on their own past.

Everything seems to be literally swallowed, not influencing any time, not part of any register or database. Your images seem to be announcing a beginning and an end and in between: something. Maybe the possibilities of a soundless keyboard, of an lonesome developing bath, of watercolours (a term only used in childhood), of a pattern-card that doesn’t trigger the thought nor the need of colour. These possibilities behave as frames in a film: defined and finite but innumerable for the naked eye. It is this kind of inaccessibility that makes ‘Rear Window’ (1954) so claustrophobic, the almost seizable echo of the other side of a valley or a courtyard.

To conclude, I notice the flowers in your book, for example the strange doubles on pages 7 and 18 that irresistibly remind me of -Hitchcock again- ‘Vertigo’ (1958) and the scene in which James Stewart observes the Carlotta-portrait and Kim Novak sitting in front of it (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Beac86mN8XM) and remember: history can remind us that one thing leads to another!

Johan De Wilde

september 2010

On the way to the miracle hosiery shop …

Quote “Tram Race ‘: Aleid Truijens in A bit of destiny” (2002, broken Workers Pers.)

Rik De Boe (°1964, Ninove, Belgium) makes drawings and drawings. By contesting the division between the realm of memory and the realm of experience, De Boe absorbs the tradition of remembrance art into daily practice. This personal follow-up and revival of a past tradition is important as an act of meditation.

His drawings are often classified as part of the new romantic movement because of the desire for the local in the unfolding globalized world. However, this reference is not intentional, as this kind of art is part of the collective memory. By putting the viewer on the wrong track, he tries to create works in which the actual event still has to take place or just has ended: moments evocative of atmosphere and suspense that are not part of a narrative thread. The drama unfolds elsewhere while the build-up of tension is frozen to become the memory of an event that will never take place.

His works are given improper functions: significations are inversed and form and content merge. Shapes are dissociated from their original meaning, by which the system in which they normally function is exposed. Initially unambiguous meanings are shattered and disseminate endlessly. By referencing romanticism, grand-guignolesque black humour and symbolism, he creates work through labour-intensive processes which can be seen explicitly as a personal exorcism ritual. They are inspired by a nineteenth-century tradition of works, in which an ideal of ‘Fulfilled Absence’ was seen as the pinnacle.

His collected, altered and own works are being confronted as aesthetically resilient, thematically interrelated material for memory and projection. The possible seems true and the truth exists, but it has many faces, as Hanna Arendt cites from Franz Kafka.

a biography generated through 100 words or 500 letters

http://www.500letters.org/index.php